Chew card versus Infrared camera efficiency when hunting the last few possums – A mainland New Zealand eradication tool use lesson

By Tim Sjoberg, Taranaki Mounga Research and Innovation Lead

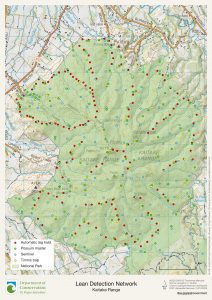

In order to successfully indicate whether Predator Free 2050 projects have completely removed possums from specific areas, in 2019 baited chew cards were trialled against Infrared (IR) cameras to quantify detection sensitivity and detection probabilities. The study site was the Kaitake Range, approximately 2400 hectares of coastal podocarp forest, located on the north western section of Egmont National Park. The study measured possum survivorship and tool efficiency after a dual aerial application which occurred May – October 2019.

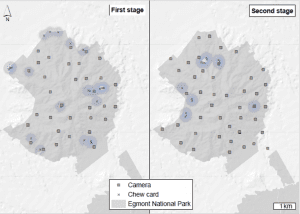

Stage One detection was undertaken from 13 May – 2 June (13 days post aerial application), while stage two was undertaken between the 4 – 24 November (11 days after stage two aerial operation). In order for these results to be consistent, the IR cameras were already in place. Extra cards and cameras were used in the second stage detection phase as these devices provided increased visibility within a small side block of continuous forest that was identified as having a high possum reinvasion risk.

Stage two chew cards were deployed with peppermint flour blaze to increase their sensitivity to possum detection.

A total of 883 aniseed chew cards (10 x 10 cm sized) were deployed every 100 metres along 85 kilometres of track within the Kaitake Range after stage one of the aerial operation. While 943 peanut butter cards were used along 91 kilometres of track (again spaced every 100 metres, often in the same location) after stage two. During stage two card deployment, flour blaze (5:1 flour/icing sugar with ~25 ml Hansels peppermint essence/6 kg) was used above each card to increase its sensitivity to possum encounter and interaction.

IR cameras (15 LTL Acorn 5210A, 940 nm infrared cameras and 48 Browning Dark Ops Hd Pro X, 940 nm infrared cameras) were deployed in ~42 hectare grid throughout the Kaitake Range. Sixty cameras were used in stage one while 63 were used in stage two. Upon camera activation, a picture was taken and a five minute delay occurred before a further picture could be made. Cameras were attached to tree trunks ~40 centimetres off the ground and faced towards the lure ~ three meters distance away. For monitoring after stage one aerial application chew cards where used as the possum lure while stage two had Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) Motolure which dispersed a small volume of egg mayonnaise every 24 hours.

Each chew card cost $0.35 plus a single nail, field staff can carry, install and service hundreds per day whereas cameras, rechargeable batteries and SD cards cost ~$500 each and the time to review the footage can be extensive in terms of labour.

Results

Stage one aerial operation: 13 may – 2 June 2019

Of the sixty cameras deployed over the 21-day detection period following stage one operation, fifty cameras recorded continually while ten occurred faults at some stage. Cameras recorded 883 pictures over 1092 camera nights (24 hour time blocks) resulting in 133 possum events. Over the same 21 day period, 18,543 chew card nights recorded 29 possum chews (two chews was recorded at same location). Twelve of these possum chews were within 300 m of the bush boundary and one small area had four cards chewed in a clustering pattern.

Interestingly, chew cards acting as the only camera station lure were not being ‘chewed’ by possums, animals were simply attracted by the visual novelty or walking past not interested in the chew card.

Stage two aerial operation: 4 – 24 November 2019

63 cameras yielded 1950 pictures containing 211 possum events (24 hour presence or absence count) within 1225 camera days. We encountered issues with six of the 63 cameras, mostly human error with incorrect camera setting for time/date stamp records. Of the 943 chew cards deployed over the same time period (19,803 nights between 11 November – 1 December), only 16 possum chews were recorded on the cards.

Table 1 below: Detection probability of camera stations compared to chew cards within the Kaitake Range after stage one and two aerial operations.

| Device | Number of devices | Detection duration (days) | Detection probability over 21 days |

| Stage 1 camera | 60 | 1092 | 12% |

| Stage 1 chew cards | 883 | 18,543 | 0.15% |

| Stage 2 camera | 63 | 1225 | 17.2% |

| Stage 2 chew cards | 943 | 19,803 | 0.08% |

Map of possum records from cameras and chew cards after stage one and stage two aerial operations, Kaitake Range.

Discussion

So why did chew cards, an industry best practice tool with a proven track record at detecting possums result in such low probability of detection? There are several theories for these results, all of which are complex and not fully understood. The first hypotheses is the inability of an acute toxin to completely remove possums compared to traditional eradication toxins (anticoagulants), while the second highlights the major difference in ‘active’ versus ‘passive’ detection tools.

It is not completely clear why aerial 1080 delivered via an island aerial eradication method failed to remove all or substantially more possums than trial results achieved, although this result mirrors Nugent et al. (2019) study in which their dual aerial 1080 sowing also concluded in not eliminating all possums. We hypothesize that the possums in the Kaitake Range that either survived toxic exposure, or did not consume any toxic pellets were extremely neophobic and subsequently reluctant to bite on baited chew cards. Even when baited with lures not associated with the toxic operations. Had pre-operational monitoring been undertaken with chew cards occurred, we expect that more chew cards would have been chewed by possums. Although Wax tags were not used, we believe the results would have been similar regardless of tool use.

These results also dramatically expose the limitation of ‘active’ detection devices (chew cards requiring an animal to bite, leaving their tooth marks) compared to ‘passive’ devices (simply walking past) within attempts to completely remove possums from mainland New Zealand. The unwillingness of the survivor possums to bite into a chew card is concerning, but also evaluates the probability of detection and value of cameras regardless of the associated cost in time, money and investment in camera instalment skills.

It raises questions regarding all traditional detection or monitoring tools to actual pest numbers. Research led by the Department of Conservation and universities, has now started to focus on developing a standardised camera methodology for measuring pest species abundance, this will provide greater visibility of pest abundance as a repeatable measurement but will differ in design methodology and time duration from eradication attempts.

This trial demonstrates that even under current best practice, operational success is never guaranteed. More research and investment is also required to develop artificial intelligence or software programmes that can reduce the intensive labour need to currently review all camera footage while constant human vigilance is required to ensure that cameras are programmed and installed correctly.

Reference

Nugent G., Morriss G., and Warburton B. 2019. Attempting local elimination of possums (and rats) using dual aerial 1080 baiting. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43:2.