What Now NZ spent some time with our Science and Innovation Lead Tama Blackburn and the awesome Korban Knock in the ngahere. Watch their adventure (and hilarious one-liners) as they check out the technology we use on our maunga!

Articles

Tipunakore Rangiwai – At home restoring his tupuna maunga

Wednesday, August 11th, 2021Kaiwhakamōkihi/Trainee Ranger Tipunakore Rangiwai (Taranaki Iwi) is helping to restore his maunga. See his journey and how he has positively impacted our Taranaki Mounga Project. Tipunakore joins the project from START Taranaki – a programme that supports young men in

Rāhui on Taranaki Mounga lifted

Friday, May 14th, 2021The rāhui was lifted at 7 am on Friday 14 May and all operations and activities on the mountain can recommence.

In respect for the passing of the two climbers near the summit last week, a rāhui had been in place since Wednesday 5 May.

Ngā Iwi o Taranaki and DOC thank the public for respecting the rāhui, an important cultural custom for mana whenua.

Iwi representatives expressed their sympathy for the families who lost loved ones last week, and their appreciation for those personally involved in the rescue and recovery operation.

DOC urges all climbers, trampers, and visitors to the mounga to follow the Land Safety Code advice set out by the Mountain Safety Council, which can be found on the DOC website.

Kiwi returns to the Kaitake Range

Thursday, April 29th, 2021TV One – Seven Sharp

The return of kiwi after an absence of decades is thanks to the massive community effort to reduce predators numbers on the Kaitake Range.

Watch the Seven Sharp article here.

Fiona Gordon from Rotokare Scenic Trust, Tane Manu of Ngā Mahanga a Tairi and Sian Potier from the Taranaki Kiwi Trust.

Photo – Jenny Feaver.

Wētā thrive on Taranaki Maunga when rats absent, study showed

Thursday, March 11th, 2021

Wētā motel. Photo – Fern Kumeroa.

Taranaki Daily News

Research projects by two post-graduate university students have revealed more about the dietary behaviour of predators on Mt Taranaki.

Massey University zoology graduate Fern Kumeroa, and Lincoln University natural resource management and ecological engineering graduate Katie Coster were involved in separate studies with similar aims during the summer.

Kumeroa, of Ngāti Ruanui, researched the effect rats had on wētā populations in the region’s national park Te Papakura o Taranaki.

The Ngā Pae o Te Maramatanga scholarship recipient worked with the Taranaki Mounga project to set up 17 ‘wētā motels’, or artificial shelters, on tree trunks within a 1000ha block in the national park, for wētā to crawl into, safe from predators.

Fifty-eight tracking tunnels were placed inside, and outside, the control block, to gauge whether insect and predator activity increased, or decreased, the further away the shelters were placed from the control area.

Previous studies have found invertebrate populations, such as wētā, respond well to rodent control and increase in number with fewer rodents around.

Footprint tracks, monitored by Kumeroa over an eight-week period, showed wētā tracks increased inside the A24 block, and decreased the further away from the block.

The opposite was true for rats, with numbers down within the block, and more away from it.

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.

Noisy tech project lures a win for students

Friday, February 26th, 2021

Auroa School students Ella McKenna, Sophie van den Brand, Lily Malo and Maddi Goodchap have won a national title for their science project making sound lures to attract predators to traps. Photo – Andy Jackson.

Taranaki Daily News

When it comes to trapping the predators that harm New Zealand’s native wildlife, a group of South Taranaki students are making a big noise.

Instead of only relying on food as bait, students from Auroa School, near Hāwera, have made sound lures, electronic devices that use noises such as baby birds cheeping, to attract predators including stoats and possums into traps.

The lures are now being trialled on farms near the school, at the New Plymouth Airport, on Taranaki Maunga by the Department of Conservation, and by private trappers in the McKenzie Country and the West Cost of the South Island.

And the work has also won the national Tahi Rua Toru Tech challenge, a team-based digital technology competition for schools.

Sophie van den Brand, 11, Lily Malo, 11, Maddi Goodchap, 10, and Ella McKenna, 11, are the second team of year 6 students from Auroa School to work on the project, which is led by deputy principal Myles Webb.

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.

Kiwi are coming back to the Kaitake Range

Monday, February 8th, 2021

A combined effort to bring kiwi back to the Kaitake Range. Photo – Andy Jackson.

Taranaki Daily News

Adult kiwi are soon to be re-released onto Taranaki’s Kaitake ranges for the first time, prompting a warning for dog owners to keep their pets leashed around the park area.

The kiwi are to be released onto the range in about three month’s time, following extensive trapping and aerial 1080 operations that have decimated rat, mustelid and possum numbers in the Kaitake and Pouakai ranges.

The re-release is a significant milestone in the Restore Kaitake campaign, undertaken as part of the Taranaki Regional Council’s Towards Predator-Free 2050 programme.

Kaitake Conservation Trust member Robbie McGregor, who helps set predator traps on the Te Papakura o Taranaki boundary, said people should be vigilant in having their pet dogs leashed during the release period.

“It’s definitely a ‘no go’ area for dogs with kiwi around,” he said.

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.

Rat trapping network helping offshore island’s endangered seabird survival

Monday, January 4th, 2021

Tane Manu (Nga Mahanga a Tāiri), Wayne Capper (Te Kāhui O Taranaki/ Conservation Department), and Sera Gibson (Taranaki Mounga) with Mataroa Island in background. Photo – Andy Jackson

Taranaki Daily News

After years of sporadic pest control efforts, an intensive barrier of traps has reduced numbers of rats and other predators on Nga Motu/Sugarloaf Islands, offshore of New Plymouth, to almost zero.

Around 19 species of seabirds, numbering around 10,000 birds in total, including endangered shearwaters, nest on three of the five offshore islands – Mataora/Round Rock, Pararaki and Motuotamatea/Snapper Rock – within the Tapuae Marine Reserve, close to Port Taranaki.

Intensive trapping over many years by the Department of Conservation, and more recently in collaboration with Taranaki Mounga, Ngāti Te Whiti hapu and Ngā Mahanga a Tāīri, has almost wiped out rats and mice on the islands.

Since October 2020, only four rats have been trapped on Mataora Island, while no sign of predators had been detected on Pararaki and Motuotamatea during routine weekly re-servicing of 10 specially designed traps, Taranaki Mounga project manager Sera Gibson said.

The traps contain a DC200 stoat trap, a mouse trap and A24 resetting trap, as well as a rat lure formulated by pest control company Zero Invasive Predator (ZIP) to reduce manual servicing.

The reduction in predator numbers meant the group will now re-service traps every fortnight instead of weekly, she said.

Mataora is the closest island to the mainland and low tide provided easy access for rats and other predators to target nesting seabirds, Gibson said.

Together with a 100-trap network and bait stations, in collaboration with New Plymouth District Council, and Francis Douglas Memorial College students, and Taranaki Mounga and iwi, the predator-trapping programme had further significantly reduced pest numbers around Centennial Drive and Paritutu Rock on the mainland above the port, she said.

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.

Chew card versus Infrared camera efficiency

Friday, November 27th, 2020Chew card versus Infrared camera efficiency when hunting the last few possums – A mainland New Zealand eradication tool use lesson

By Tim Sjoberg, Taranaki Mounga Research and Innovation Lead

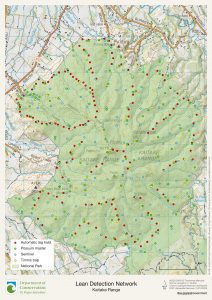

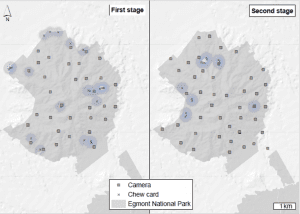

In order to successfully indicate whether Predator Free 2050 projects have completely removed possums from specific areas, in 2019 baited chew cards were trialled against Infrared (IR) cameras to quantify detection sensitivity and detection probabilities. The study site was the Kaitake Range, approximately 2400 hectares of coastal podocarp forest, located on the north western section of Egmont National Park. The study measured possum survivorship and tool efficiency after a dual aerial application which occurred May – October 2019.

Stage One detection was undertaken from 13 May – 2 June (13 days post aerial application), while stage two was undertaken between the 4 – 24 November (11 days after stage two aerial operation). In order for these results to be consistent, the IR cameras were already in place. Extra cards and cameras were used in the second stage detection phase as these devices provided increased visibility within a small side block of continuous forest that was identified as having a high possum reinvasion risk.

Stage two chew cards were deployed with peppermint flour blaze to increase their sensitivity to possum detection.

A total of 883 aniseed chew cards (10 x 10 cm sized) were deployed every 100 metres along 85 kilometres of track within the Kaitake Range after stage one of the aerial operation. While 943 peanut butter cards were used along 91 kilometres of track (again spaced every 100 metres, often in the same location) after stage two. During stage two card deployment, flour blaze (5:1 flour/icing sugar with ~25 ml Hansels peppermint essence/6 kg) was used above each card to increase its sensitivity to possum encounter and interaction.

IR cameras (15 LTL Acorn 5210A, 940 nm infrared cameras and 48 Browning Dark Ops Hd Pro X, 940 nm infrared cameras) were deployed in ~42 hectare grid throughout the Kaitake Range. Sixty cameras were used in stage one while 63 were used in stage two. Upon camera activation, a picture was taken and a five minute delay occurred before a further picture could be made. Cameras were attached to tree trunks ~40 centimetres off the ground and faced towards the lure ~ three meters distance away. For monitoring after stage one aerial application chew cards where used as the possum lure while stage two had Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) Motolure which dispersed a small volume of egg mayonnaise every 24 hours.

Each chew card cost $0.35 plus a single nail, field staff can carry, install and service hundreds per day whereas cameras, rechargeable batteries and SD cards cost ~$500 each and the time to review the footage can be extensive in terms of labour.

Results

Stage one aerial operation: 13 may – 2 June 2019

Of the sixty cameras deployed over the 21-day detection period following stage one operation, fifty cameras recorded continually while ten occurred faults at some stage. Cameras recorded 883 pictures over 1092 camera nights (24 hour time blocks) resulting in 133 possum events. Over the same 21 day period, 18,543 chew card nights recorded 29 possum chews (two chews was recorded at same location). Twelve of these possum chews were within 300 m of the bush boundary and one small area had four cards chewed in a clustering pattern.

Interestingly, chew cards acting as the only camera station lure were not being ‘chewed’ by possums, animals were simply attracted by the visual novelty or walking past not interested in the chew card.

Stage two aerial operation: 4 – 24 November 2019

63 cameras yielded 1950 pictures containing 211 possum events (24 hour presence or absence count) within 1225 camera days. We encountered issues with six of the 63 cameras, mostly human error with incorrect camera setting for time/date stamp records. Of the 943 chew cards deployed over the same time period (19,803 nights between 11 November – 1 December), only 16 possum chews were recorded on the cards.

Table 1 below: Detection probability of camera stations compared to chew cards within the Kaitake Range after stage one and two aerial operations.

| Device | Number of devices | Detection duration (days) | Detection probability over 21 days |

| Stage 1 camera | 60 | 1092 | 12% |

| Stage 1 chew cards | 883 | 18,543 | 0.15% |

| Stage 2 camera | 63 | 1225 | 17.2% |

| Stage 2 chew cards | 943 | 19,803 | 0.08% |

Map of possum records from cameras and chew cards after stage one and stage two aerial operations, Kaitake Range.

Discussion

So why did chew cards, an industry best practice tool with a proven track record at detecting possums result in such low probability of detection? There are several theories for these results, all of which are complex and not fully understood. The first hypotheses is the inability of an acute toxin to completely remove possums compared to traditional eradication toxins (anticoagulants), while the second highlights the major difference in ‘active’ versus ‘passive’ detection tools.

It is not completely clear why aerial 1080 delivered via an island aerial eradication method failed to remove all or substantially more possums than trial results achieved, although this result mirrors Nugent et al. (2019) study in which their dual aerial 1080 sowing also concluded in not eliminating all possums. We hypothesize that the possums in the Kaitake Range that either survived toxic exposure, or did not consume any toxic pellets were extremely neophobic and subsequently reluctant to bite on baited chew cards. Even when baited with lures not associated with the toxic operations. Had pre-operational monitoring been undertaken with chew cards occurred, we expect that more chew cards would have been chewed by possums. Although Wax tags were not used, we believe the results would have been similar regardless of tool use.

These results also dramatically expose the limitation of ‘active’ detection devices (chew cards requiring an animal to bite, leaving their tooth marks) compared to ‘passive’ devices (simply walking past) within attempts to completely remove possums from mainland New Zealand. The unwillingness of the survivor possums to bite into a chew card is concerning, but also evaluates the probability of detection and value of cameras regardless of the associated cost in time, money and investment in camera instalment skills.

It raises questions regarding all traditional detection or monitoring tools to actual pest numbers. Research led by the Department of Conservation and universities, has now started to focus on developing a standardised camera methodology for measuring pest species abundance, this will provide greater visibility of pest abundance as a repeatable measurement but will differ in design methodology and time duration from eradication attempts.

This trial demonstrates that even under current best practice, operational success is never guaranteed. More research and investment is also required to develop artificial intelligence or software programmes that can reduce the intensive labour need to currently review all camera footage while constant human vigilance is required to ensure that cameras are programmed and installed correctly.

Reference

Nugent G., Morriss G., and Warburton B. 2019. Attempting local elimination of possums (and rats) using dual aerial 1080 baiting. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43:2.

Taranaki farm couple’s 25 year war of the roses with possums

Saturday, August 29th, 2020

Taranaki dairy farmer Fiona Henchman can now smell her roses. Photo – Andy Jackson.

Taranaki Daily News

Taranaki dairy farmer Fiona Henchman can now declare victory in a personal war of the roses she has waged against possums for a quarter of a century.

With husband John she has fought a backyard battle against thousands of possums hopping over the boundary fence from Egmont National Park to munch on fruit trees, grass pasture and treasured climbing roses.

Pasture near the national park boundary has also taken a hammering, with the pests’ eating habits leaving the ground resembling a mown strip.

Anything the couple attempted to plant and grow on the 130ha Upper Weld Road property was gnawed to the stem by the nocturnal marauders, she said.

The only nutrient area untouched was the vegetable garden.

“I’m not a serious rose grower. It was just that the possums wouldn’t let me grow anything. It’s been a war ever since.”

Although thousands of possums, some weighing up to 4.5kgs, were killed, with their fur sold to dealers to fund eradication, the pests kept coming, she said.

To combat the never-ending raids, Henchman wrapped rose buds and stems in glad wrap, laid poison cyanide and phosphorous baits, set traps, used thermal imaging detectors and attached ‘red dot’ night vision to a rifle, while leaving the window open at night, for a clear shot when they came on the verandah.

“We put a lot into getting rid of them – I called it saturation bombing – but it made no difference. The possums still stripped everything bare, but I wasn’t giving up.”

Henchman now thinks the possums are on the run after a concentrated trapping and aerial 1080 programme during the past 12 months in the Kaitake Ranges and Egmont National Park, work co-ordinated by the Department of Conservation, Taranaki Mounga and Towards Predator-Free Taranaki (TPFT).

“They came back a little during lockdown when the traps were not being checked, but now we have contractors on the farm every day monitoring the traps, and there has been a huge difference,” she said.

“The tui among the banksia are deafening.

“They’re (possums) still around but they are well under control.”

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.

Kaitake Range possum trap network

Sunday, August 16th, 2020Lessons from our Kaitake Range possum trap network – Why not to use single set removal traps for possum eradication attempts?

By Tim Sjoberg, Taranaki Mounga Research and Innovation Lead

In 2016, the New Zealand government announced the ambitious aim of removing rats, possums and stoats from mainland New Zealand by the year 2050 (Predator Free 2050). To achieve this large-scale eradication, aerial tools are needed to remove predators from inaccessible and larger continuous forested landscapes. This, while follow up ground predator control tools to remove remnant animals. For this to be successful, the tools used need to be socially acceptable, cost effective and scalable.

In this summary we explore why single set removal traps will not achieve compete removal of possums from continuous forest in Taranaki and investigate other control tool options and their success to date.

Restore Kaitake is an ongoing pilot programme to completely remove possum from ~ 5000 hectares of land in and surrounding the Kaitake Range. This area includes 2,300 hectares of the Kaitake Range, 2,000 hectares of Kaitake farmland and Oākura town which includes residential properties, a school public reserves and walkways.

This project was initiated by Taranaki Mounga Project (TMP), Department of Conservation (DOC) and the Taranaki Regional Council (TRC) as part of the Taranaki Taku Tūranga – Towards Predator-Free Taranaki, with the overall lead being TRC. As part of this operation, TRC intensely controlled possums from the surrounding ~2,500 hectares of the Kaitake Range with wide range of methods (live capture trapping, removal trapping, bait stations and thermal assisted night predator control etc). While TMP undertook an aerial control 1080 operation to initially knock down possums, a removal trap network was actioned with the aim of removing any surviving possums.

The design of the network started in mid-2018, at this early stage in mainland eradication attempts by Predator Free 2050 (PF2050) we took lessons from past operations and the best available advice from technical advisors. The concept of installing one removal trap every 50 hectares was suggested to be sufficient to expose all possums (and hypothetically remove them) within a low-density possum landscape, as possum home range size increases dramatically after an effective aerial operation. To maximise operational success we decided to trial a high density trapping network. This consisted of 294 single set possum removal traps (143 Sentinal, 121 Possum Master and 30 Timms possum trap), set within a ~12.5 hectare grid covering the Kaitake Range and any surviving animals home range.

These three trap types were chosen because of their high capture rates, ease of service, different coloured materials, and previous history with minimal non-target by-catch. Care was taken to locate and install traps in the most suitable “trapping tree” within the constraints of steep country or inaccessible areas. Because of weather delays, some traps were installed and left unbaited up to 6 months before the aerial operations begin.

After the first application of the double (or dual) aerial 1080 operation had occurred and the detection network consisting of cameras (n = 63) and chew cards (n = 900, white corflute impregnated with lure) indicated a sufficient reduction of possums. We baited and set the removal trap network on the Kaitake Range to determine if we could remove the remaining possums without the need for the second stage of the aerial application.

Between the first and second aerial operation, we set all traps starting from seven days after the aerial application and finished 16 days after the application. Traps were baited with Connovation ‘smooth’ lure and flour blaze (5:1 flour and icing sugar lured with ~ 50 ml of Hansells peppermint essence). Both lures are industry standard and good attractants/bait to possums. This trapping network was serviced five times between day 16 to day 70 after the aerial application, with the average service time being 10 1/2 days. Each service consisted of refreshing the trap lure and flour blaze, chew cards and serving the cameras. The above-mentioned lure was used for the first four trap services, the last trap service was baited with a mixture of peppermint, cinnamon, mixed herbs held with a flour, icing sugar and sunflower oil matrix.

From the ~15,876 trap nights, this pilot network removed 18 possums over ~54 nights. We estimated 600 possums left within the Kaitake Range after the double (or dual) aerial 1080 operation was completed. When evaluated to the self-reporting leg hold network (installed since late-2019, using 190 leg hold traps), this network has removed 108 possums from the Kaitake Range over a 54 night periods between 1 May to 23 June 2020 (~10,260 trap nights). It should be noted that this trapping period occurred following New Zealand’s March/April 2020 Level 4 Covid-19 lockdown. During this time no leg hold traps were actively set to capture, meaning trap lure may have increased in novelty through a two month period of no trapping.

We hypnotise that the single set removal trap network was ineffective at removing possums compared to the leg hold network for several reasons. Firstly the instalment of traps (unbaited and unset) for long periods (up to six months) before setting live could have allowed the novity of the traps to diminish. A better approach might have been stashing traps near or at track junctions and setting on trees once aerial operation had been undertaken to increase novity for surviving possums. Secondly, the intensive use of chew cards might have caused a distraction to surviving possums as cards where positioned along all trap lines at 100 m intervals. Thirdly, the lures used were not attractive enough given the higher abundance of readily accessible food resources available to surviving possums after stage one aerial operation. And lastly, more animals were captured than found however these were removed by members of the public before staff serviced the trapline.

We place more weight to the first two options as subsequent possums have been caught on the Kaitake Range using the above-mentioned lures, also the small number(s) of traps cleared of animals by members of public would have little impact on the trap networks results (i.e. 18 possums over 15,876 trap nights versus 108 possums caught over smaller trap nights from the leg hold traps).

Ultimately, this trial demonstrates that traditional possum removal traps, even when deployed at high density (i.e. every 12.5 hectares), using three different trap types and baited with industry standard lures, will not completely remove possums from continual forests in Taranaki. We believe more sensitive control tools that require less manual bait refreshment need to be developed in order to achieve PF2050 for possums and although the self-reporting leg hold network is capturing possums at higher frequency than single set removal traps, the labour requirements of install and maintenance needs to be greatly reduced in order for this tool to be scalable.

The Taranaki Mounga Project would like to thank TPFT, DOC, along with our Taranaki Mounga ranges and the Kaitake community for being so accommodating as we carried out this work. These learnings have been shared with key research and predator control groups to help with their large-scale predator possum eradication operations from inaccessible and larger continuous forested landscapes.

Trev’s new job is protecting whio from predators

Sunday, August 2nd, 2020

START Taranaki Mounga trainee Trevor Walker, 16, with his mother Leonie Schuler, wants to lead his own trapping project in future. Photo – Simon O’Connor.

Taranaki Daily News

A South Taranaki teenager who outgrew the classroom walls has found his calling helping protect the whio/blue duck population in Egmont National Park.

Trevor Walker’s efforts have been so successful that a whio, one of more than 200 in the park, was named after him.

Trevor , 16, is one of two first year START trainees working with the Taranaki Mounga predator-free programme.

START, or Supporting Today’s At Risk Teenagers, established in 2003 and based in Kaponga, has partnered with Taranaki Mounga predator-free project to mentor and provide employment pathways to young people.

Walker spent a year with the START basic programme before joining the project, learning how to build and set predator traps, cutting tracks and lay trap lines in the national park boundary.

“I used to go into the bush with my uncles but it was still a bit of a mission building the traps and setting trap lines up to 15km,” he said.

“It was hard cutting the tracks and heavy work carry ing the traps across streams.

“There were a lot of days walking through the bush in wet boots from crossing streams.”

Working on his own, Walker built 300 DOC200 wooden traps before helping lay out 25km of trap lines from Mangawhero Rd to protect whio along the Waingongoro, Mangawhero, Kapuni and Kaupokonui Streams on the south east boundary of the park.

Read the full Taranaki Daily News article here.